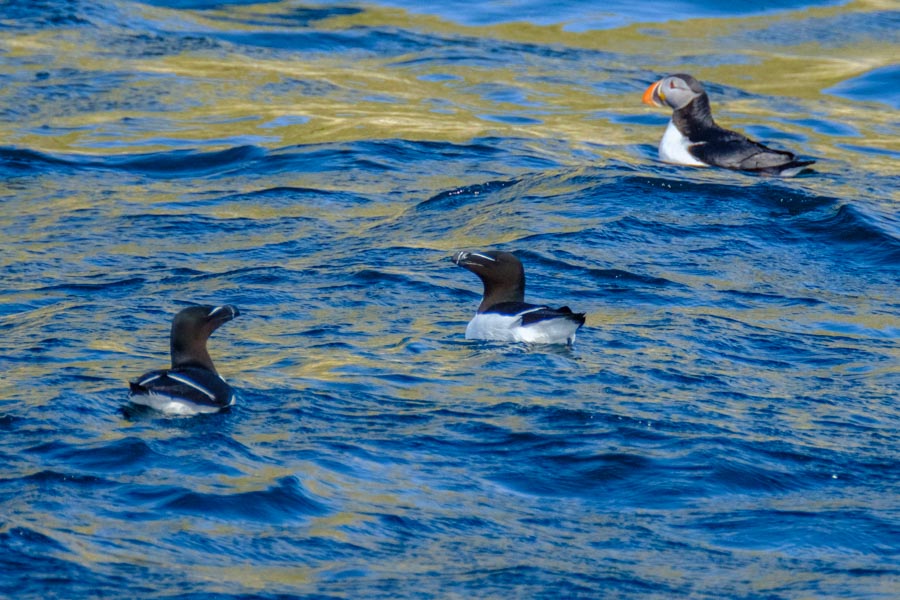

Well, I did it: went to sea in a small, heaving boat on one of the most dangerous ocean coast lines in the world and didn’t, you know, embarrass myself at the rail. Ok, the boat was bigger and the seas were clam with only a light swell and I took Dramamine before setting out and I made it just fine. And the pictures? I took a bunch and haven’t looked at them yet so we’ll see.

The day was beautiful – sunny skies and 50+ degrees. We’re told today’s was the high temperature for the year so far. We basically circled an island nature preserve and saw a large number and a large variety of birds plus a seal or two. I think I got a puffin shot but they were flying, not sitting still on a rock like a well-behaved puffin should so I’m hopeful I got one but can’t be sure.

The costal region is really subarctic, not arctic. We’re at latitude 71 degrees north, the northernmost point of the European continent but our friend the Gulf Stream keeps things toasty warm. Temps range from -10 Celsius (14 Fahrenheit) to 20 C (68 F). Lows in the wintertime further inland can reach -40 C (-40 F).

For the first time in our lives we went for a full day without seeing a single tree. Even with subarctic conditions the summer – two months long – does not support tree growth. We saw some willows perhaps six feet tall, just budding out, but nothing more than an inch in diameter. They say that 7,000 years ago, right after the last ice age, trees grew here and people lived and hunted game here. Temperatures cooled about 2,500 years ago and the game and people moved away.

Our afternoon proved to be more interesting culturally. We visited Sami people at a site somewhere between Kjollefjord and Mehamn – two small fishing villages. Both produce dried cod (“stock fish”) just like the Vikings and Hanseatic Traders did. They dry the cod for four months and sell them in southern Europe: Spain, Italy and Portugal where it is considered a delicacy when reconstituted with water.

The Sami people have lived in northern Scandinavia for over 10,000 years. Today there are about 80,000 Sami’s living in Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Russia. Traditionally the Sami peoples were reindeer herders, obtaining food, clothing and tools from reindeer herds they tended. Of the 40,000 Sami in Norway about 2,600 are actively involved in reindeer husbandry.

Reindeer herders summer in the region we visited. In August and September they move the herd to winter quarters about 150 miles inland from here. I asked our guide about the logistics of such migrations. It turns out that the herd is gathered in the fall using ATVs, trucks, dogs and even helicopters. Families cooperate in all aspects of the process; the individual owners’ herds are identified by distinctive ear cuts. The reindeer are sold to meat processors, slaughtered for local use and the remainder moved to the new location.

We visited a young woman and her boyfriend at a traditional Sami tent, both wearing traditional Sami clothing made largely from reindeer. The man sang a yoik, a traditional song that is associated with a single individual or an animal, bird or special occasion. He sang two yoiks: his yoik and his father’s yoik. The woman said that if you are alone in the wilderness and lonesome you can sing a person’s yoik and it’s like that person is next to you.

Sami’s practiced animistic practices, believing that every person, animal and object has a spirit or soul that should be venerated. Shamans told fortunes and practiced medicine. The onset of the Reformation and the influx of Christian missionaries, especially in the 18thcentury, spelled a decline in traditional religious practices. Missionaries destroyed all artifacts associated with the traditional beliefs, forbid use of Sami language and forced conversion to Christianity. As recently as the 1970s such assimilation efforts continued. The UN and world community has been sharply critical of Norway’s treatment of the Sami people as recently as 2011.

Sami culture, like many others around the world, is endangered. In Norway, however, there seems to be a firmer basis for cultural preservation than elsewhere. There are Sami schools from kindergarten through university. Samis speak nine different dialects and languages, making preservation of the culture more difficult. Norwegian is, of course, the common denominator. But the Sami culture is surely in jeopardy.

Our hosts live in houses, drive cars, have iPhones and Facebook accounts.

They spoke excellent English, described with pride their people’s past and culture yet were obviously well connected with the modern world. One can only hope.