Colombia has been in a state of violent uprising for as long as I’ve been alive. But the beginnings of violence here might be traced back to the Spanish arrival in 1449, Simon Bolivar’s fight for independence in 1819 and the Thousand Days War of 1899-1902. And the seeds of the problems spanning the last 70 years might be traced to Las Masacre de las Banneras in 1928. Have you been watching One Hundred Years of Solitude on Netflix or have you read the book? A fictionalized account of the Colombian Army’s massacre of Chiquita banana workers – 47 to 2,000, depending on who you believe, or even 3,000 as told in One Hundred Years – that was a blow against the rural workers and landholders.

But the actual start of La Violencia began with the assassination of a popular Presidential candidate, Jorge Eliecer Gaitán, which sparked riots and violence in Bogotá, called El Bogotazo. La Violencia continued for 10 years, killing 300,000 and displacing millions. It ended with a negotiated peace agreement that called for alternate presidencies with the Liberals and Conservatives serving consecutive terms – without elections.

But then in the 1960s leftist guerrilla groups formed, fighting against governmental sponsored concentration of land ownership. The two main groups, FARC and the National Liberation Army, communist-inspired, initially fought to reclaim land rights for rural peasants. The current Colombian president was a member of another guerrilla group, M19.

The government was ineffective in fighting the guerrillas, so armed illegal paramilitary groups formed to fight the guerrillas.

One might say that the guerrillas were fighting a just cause – equality for the downtrodden rural peoples. But unfortunately, the guerrillas turned to raising cocaine as a means for funding their operations. And the paramilitary groups fought for land to do the same. So the overlay of drugs fueled even greater violence. Pedro Escobar, the Colombian cartel leader, was the main channel of distribution for both sides. He became, at age 27, the second richest man in the world.

Almost 9 million people were displaced and over 1 million killed in a country of 50 million. I’ve already talked about the peace process that culminated in the accord between FARC and the government. The NLA still hasn’t signed, and last minute negotiations fell apart within the last few weeks.

Our speakers today pointed out that the murder rate in Colombia in 2017 was 24.8 per 100,000 population. Washington D.C.’s murder rate in 2023 was 80. The peace agreement, imperfect as it is, has dramatically reduced violence in Colombia.

All of this was recounted to us by two Colombians, one a representative of VAOVA and the other, Enith Moreno, was a FARC member, joining in 1984 at the age of 15. She was the fourth child of nine, her father left when she was 11 and joining was a way of survival and escape from abject poverty. She left FARC in 2001 but continued in supporting roles until 2016 when she signed the peace agreement. Her current role is as a member of MEDEPAZ, and organization dedicated to supporting 12,900 former FARC fighters as they transition to peaceful pursuits and working for peace and reconciliation in communities affected by the armed conflict.

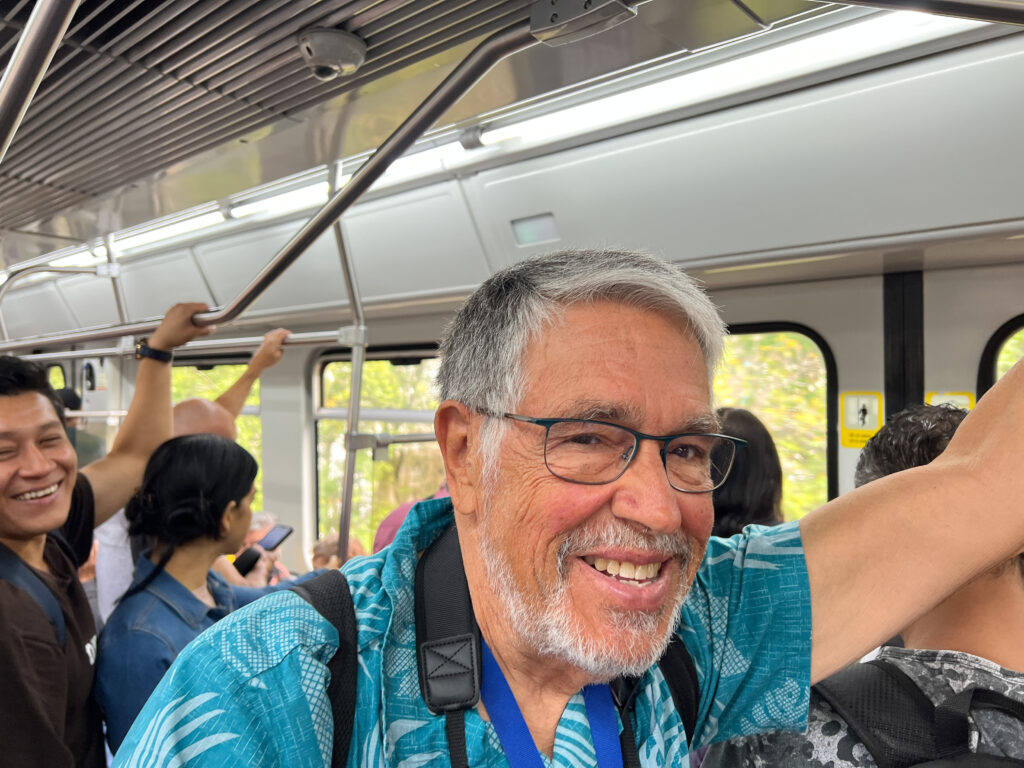

With that overview we traveled via the Metro line to the west side of town where we boarded a cable car that took us up the side of one of Medellin’s many mountain side. The metro and cable car system was put in place not so much as a tourist attraction but as a way to provide low cost transportation for informal settlements, really squatter gatherings, and low-end neighborhoods to reach jobs further down the mountain. The car we took passed over Level 1, 2 and 3 communities.

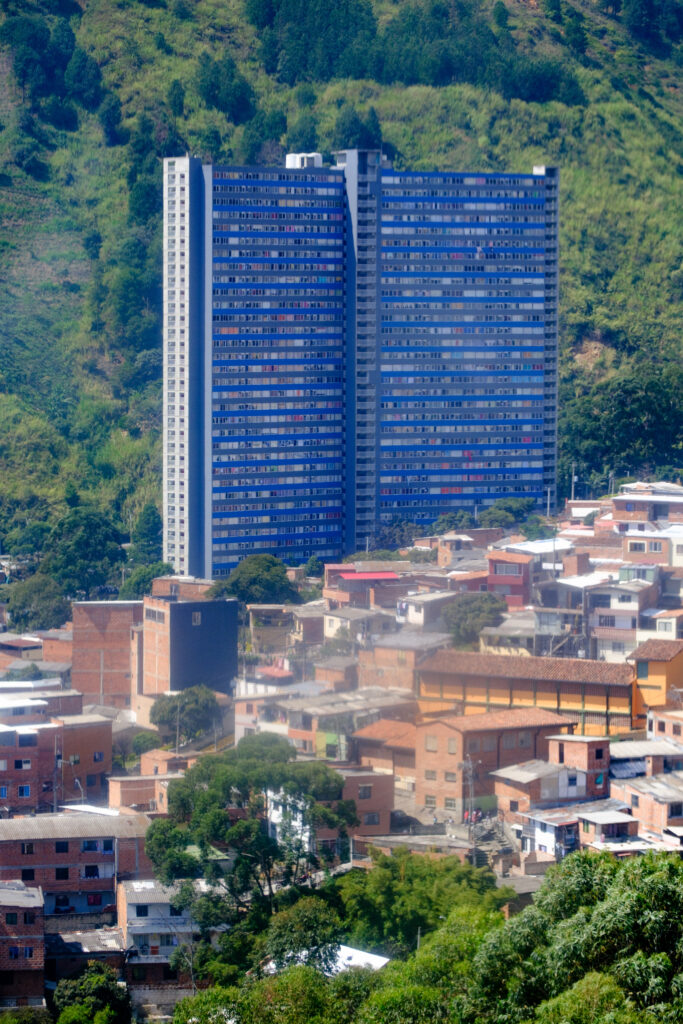

Level 1 houses are made of wood and lack virtually all services – electrical, water, sewer, schools and so on. Higher levels pick up more services and as mentioned earlier, pay more in taxes. So we began to get an answer as to how Colombia can have such a low average income – $360 per month – in a city with such apparent wealth. It all averages out: a small number of rich people are offset by large number of poor.

Then, back to the question of violence. We visited District 13, as recently as 2002 and even later the most dangerous neighborhood in Medellin, itself the most dangerous city in Colombia. It was home to FARC and other guerrilla groups. Paramilitary groups operated here. The Escobar drug cartel controlled District 13 in the 1980s. Governmental control was nil. The steep slopes and lack of a formal street system in the area made military operations virtually impossible.

Then, in October 2002 as part of the government’s crackdown on violence, District 13 was attacked by government forces using helicopters, tanks and automatic weapons., driving out guerrilla fighters and other militant groups. The operation was successful and today after investment by the government, NGOs and other countries, District 13 is now one of the most visited tourist destinations in Medellin.

Sorry for all the history stuff. I wanted to get it written down before I lost it completely.

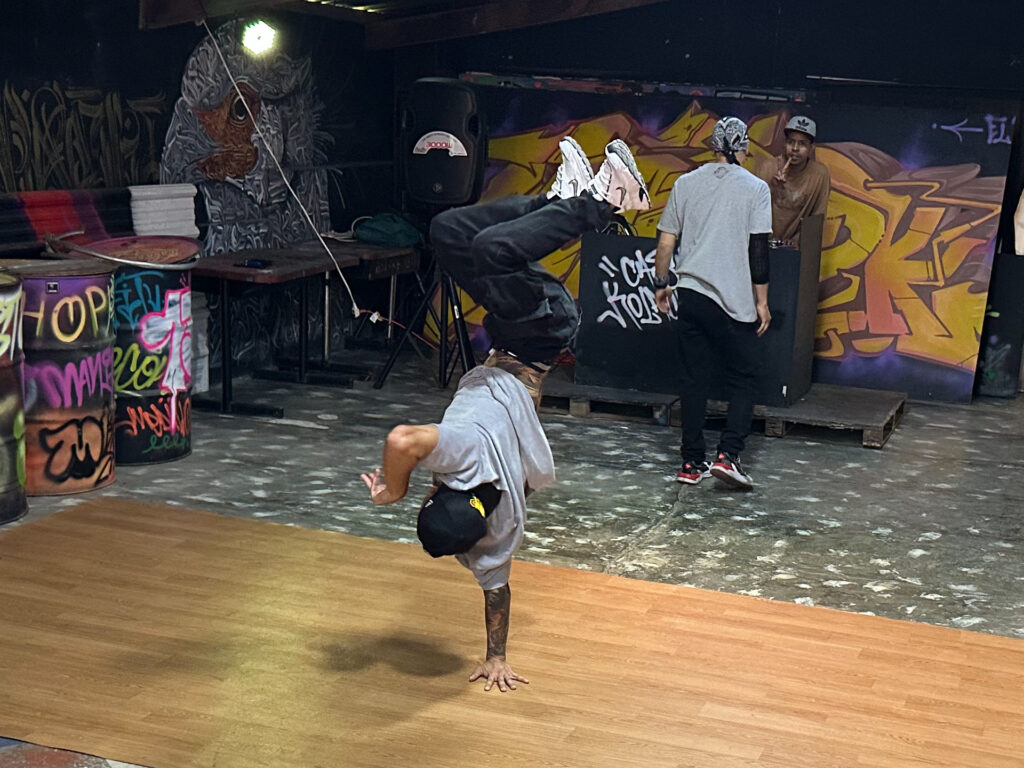

Our local guide told us that part of the reason that District 13 has recovered so well is hip hop and break dance and graffiti art. Both dance and art are outlets for youth, replacing gang membership or becoming a hit man. We walked by one break dance school and attended a performance by another.

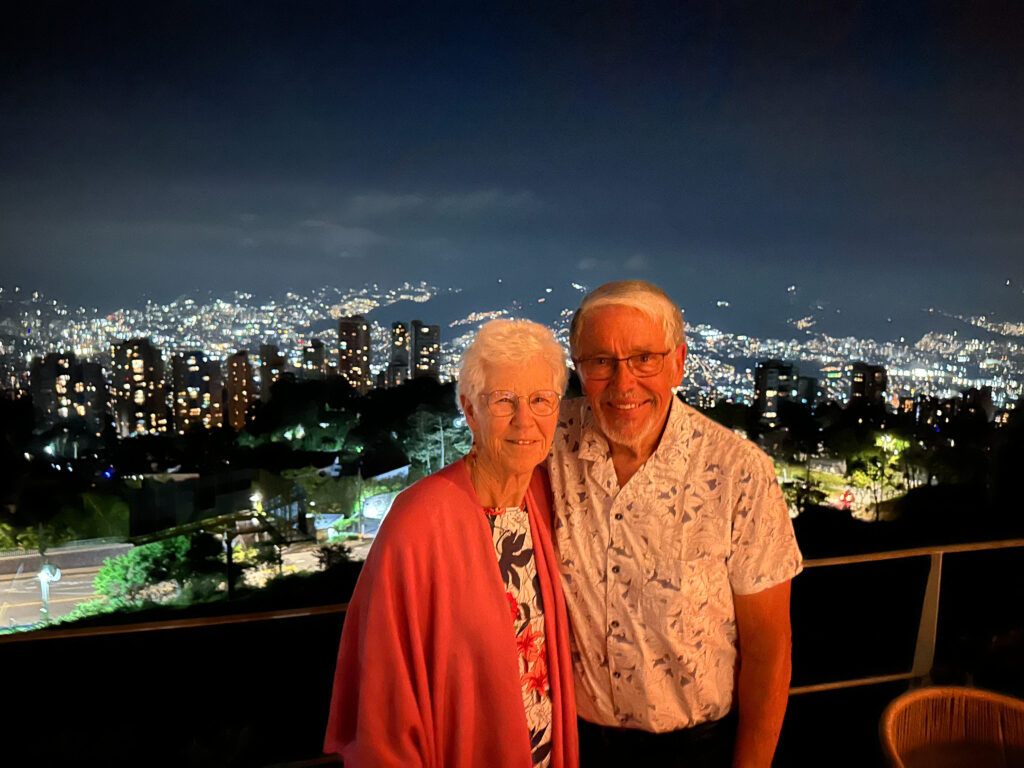

Lunch downtown and a stroll through Botero Square, home to a dozen or more sculptures donated by the artist and a quick pass through the Museo de Antioquia to see more Botero paintings and other works. Finally dinner at Ritual, high on the side of the mountain with great food and great views of Medellin.

Tomorrow, off we go to Cartagena after visiting the largest lake in Colombia and source of hydroelectric power.