Newcastle was, and still is, a coal town. Coal was used by aboriginal people for thousands of years. Soldiers taking convicts to the area found coal lying on the ground but underground coal mines have since been dug. Newcastle’s excellence ocean port solves the transport problem. And heavy industries such as steel making (now discontinued) have sprung up.

What do Newcastilians do when not working the mines? They surf. Newcastle has beaches that attract world-class surfers.

Lately, Newcastle has become a haven for folks who can’t afford the hyper inflated cost of living in Sydney, a two hour’s drive away.

Coal isn’t going to be the engine of economic growth going forward and a gritty coal town isn’t going to attract new residents and tourists. So the local government is spending multiple billions of dollars to fix the place up. They ripped out the downtown railroad tracks and put in light rail. Lots of high rise condo, apartment and office buildings are springing up, modern brick, steel and glass just like Sydney. It’s becoming a good looking place to work, live and play. And as a cruise boat terminal and as a gateway to the Hunter Valley wine region, the nascent tourism business is looking up.

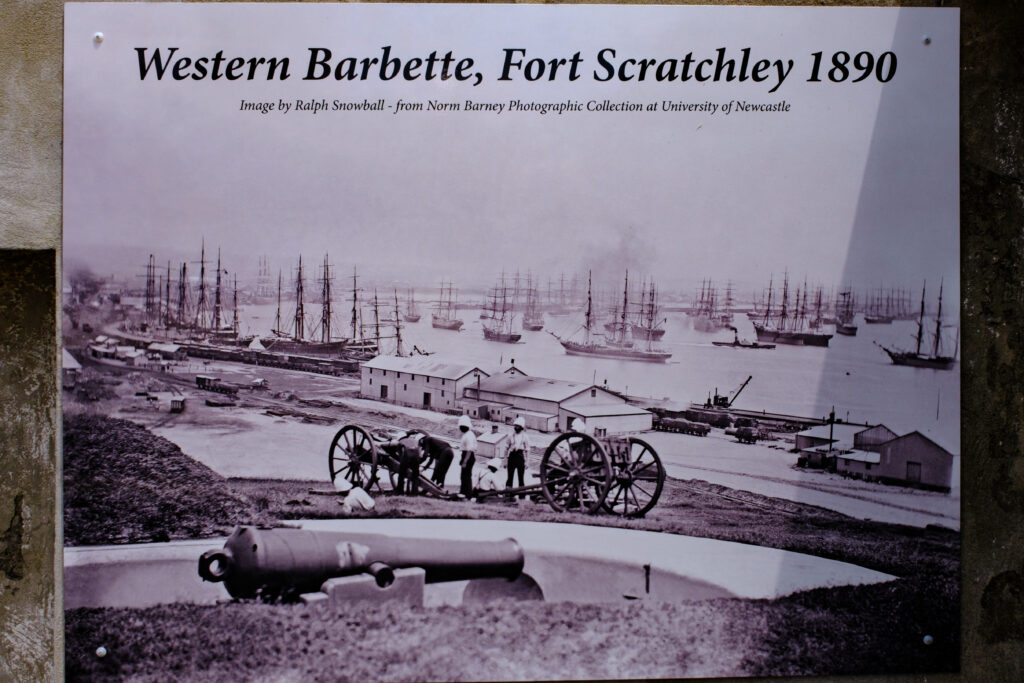

Our plan for the day was to visit Newcastle’s museum in the morning on our own and then do a guided walking tour in the afternoon. The shuttle bus dropped us at the museum which, like virtually every museum on the planet, is closed on Mondays. Plan B, suggested by a nearby info booth guy: take the light rail to Fort Scratchley. An unfortunate name but the Brigadier General Scratchley who designed the fort looks in his portrait like a proper British officer. The fort, originally built in the late 1880s to defend against a perceived threat from Russia and was significantly expanded during WWII.

Fort Scratchlely has the distinction of being the only Australian costal battery to return enemy fire in WWII. On June 8, 1942 a Japanese submarine fired several dozen rounds at the manufacturing facilities at the Newcastle dockyard. Scratchley’s six inchers fired four rounds, all missed, and the sub escaped.

We met a volunteer at the gate (free admission). He asked, “How old do you think I am?” My guess was that he looked at least 90 so I said, “I don’t know. Eighty maybe?” “I’m 97,” he responded, chest pushing out slightly. “I grew up in Liverpool during the war and went to bed every night to the sound of German bombs. I was so happy because that meant no school the next day. And I’ve got a thousand stories like that. One time there was this girl in Malay . . . “ A coworker came over and we made our escapes after inviting him to visit us in Florida. He didn’t get the girl. A guy he met by random chance on the way to Malay knew the girl and said, “Stay away from my niece or else!”

We took the light rail back to the museum and the shuttle bus back to the ship for a quick rest before the walking tour.

The bus for the walking tour dropped us near the Lumber Yard where convicts once worked. Next, we walked to the old train station, now a shopping destination. Our guide pointed out that, unlike many European cities with an “old town,” Newcastle’s old buildings are mixed in with the new. Of course “old” in Newcastle is not much more than 150 years old.

The walking tour then traversed a street one block away from the light rail street. It was a residential neighborhood, once run down but now gentrified in turn-of-the-twentieth century houses. The culmination of this not so strenuous hike was ice cream at a parlor near the beach. Great ice cream, but then again in all our travels we’ve never encountered anything but great ice cream. It took two runs of the bus to get us all back. Judy and I were unfortunate to be in the second bus. I whiled away the 30-minute delay with a wade in the chilly Pacific Ocean waters. Couldn’t find a surfboard though. Crikey.

I asked our guide if “transportation” – Briton’s practice of sending convicts to New South Whales for seven years, ten years or life – had a lasting impact. He said, yes, in at least two ways. First, the Australian accent and manner of speaking stems from the uneducated cockney accent of lower class British commoners. And the Aussie’s tendency to abbreviate words – Newcastlillians becomes Newies, Australians becomes Aussies – derives from the same street language of the convicts.

Second, Aussies practice what is termed Tall Poppy Syndrome. This is the practice of downplaying one’s elevated status in society and among friends. People want to avoid being seen as the tall poppy in the field and goes to great lengths to be one of the masses. Politicians do it. Successful business people do it. Our guide’s uncle is a multimillionaire and dresses like a bumb. This comes from the leveling effect of being a transported convict. No matter whether the person was convicted for petty theft, as many were, or a white collar crime like embezzlement or forgery, everyone suffered the same indignities and pain. To tout one’s elevated status in that situation was to bring down ridicule from fellow transporteres or extra punishment from the often sadistic overseers.

We were back on the ship in time for dinner and departure from the dock. We finished packing – bags out by 10 PM – and went to bed so as to be ready for the 5 AM entrance to Sydney Harbor. I’m typing this on the plane to Uluru (aka Ayer’s Rock) and, spoiler alert, getting up at five was well worth it. It’s going to be 104 degrees, but dry, when we get there. Most outside activities will be in the early morning or late afternoon.