Today was dedicated to the two “rocks” – Uluru and Kata Tjuṯa – literally from dawn until dark. Uluru gets all the publicity, but Kata Tjuṯa is equally interesting, if not more so. I’ll let the pictures describe what we saw but the story behind the scenery is, as is often the case, the real story. Traveling around the world to see a rock sticking up out of the desert is hardly worth the effort. The real reason for coming is to discover the people and events behind the vista.

First, I failed to mention yesterday that we’re in the middle of a genuine desert. The shots I took from the plane yesterday show first the urban sprawl of Sydney, then the Blue Mountains that for the convict-era settlers were a significant barrier to the interior, followed immediately by the vast expanse of flat, arid land punctuated by the occasional salt flat. And here in the park we’re in the middle of that desert.

Fortunately for us, this area has received significant rain in recent weeks, resulting in the lush green growth that contrasts so nicely with the orange of the sand and rock formations. The rain storms brought lightning, which caused one or more brush fires. The Anangu fire department took care of them in quick order. My observation from the plane was that the greenery didn’t start until we were perhaps 30 minutes from Uluru.

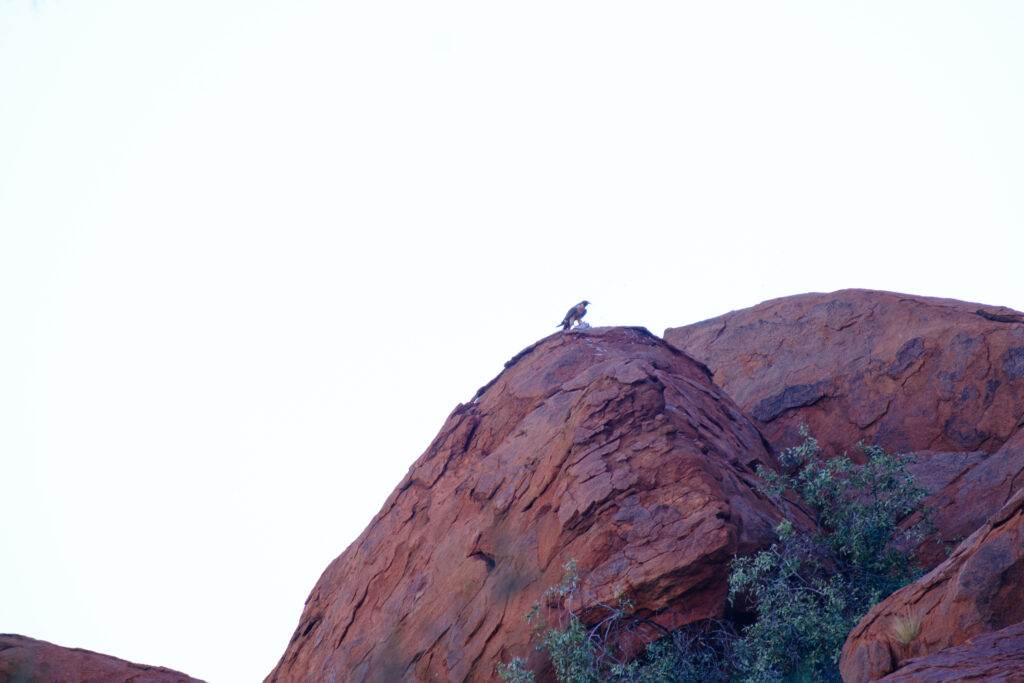

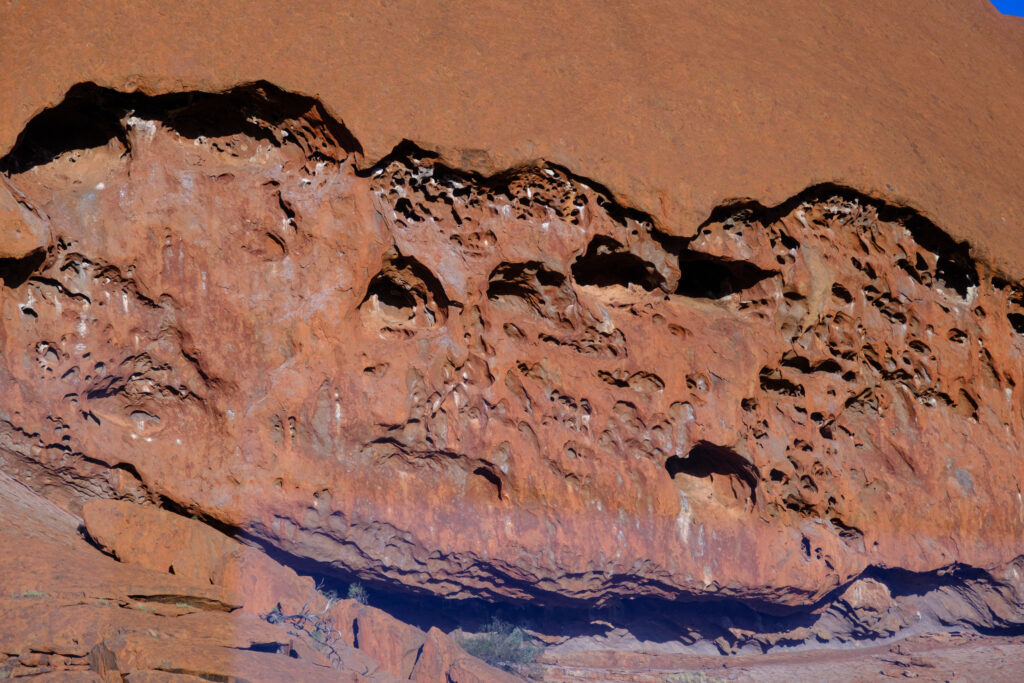

Uluru and Kata Tjuṯa both are the result of sandstone created by the weight of oceans that covered this area 500 million years or so ago and that were thrust upward by tectonic plate motion. Uluru, luck of the draw, was tilted by almost 90 degrees, meaning that what was flat under water is now vertical. Kata Tjuṯa only shifted 20 degrees and so has a distinctly different shape. Both have eroded over the millennia to produce the shapes we see today. We’re told that only 10% of Uluru’s mass, like an iceberg, is above the surface. Uluru is about 1,100 feet high. Kata Tjuṯa is around 1,700 feet.

The rocks both contain feldspar and thus their native color is grey with a bluish tint. The orange color comes from iron in the rock that has oxidized to produce the rust color we see. A magnet held against the loose soil will attract orange sand particles.

And that lush, green grass that is so prevalent and that gives such lovely accent to the rocks? Sigh, a sad story lurks beneath the surface.

Until the Anangu were forcibly ejected from their homeland in the interest of tourism back in the 1960s, they practiced controlled burning in patches of ground, something that their ancestors have done, in their culture, since the beginning of time. The burn had two benefits: controlled burning created fire barriers and also drove game from the brush for capture. But with eviction, the controlled burning stopped and after 20 years or so, in the mid 1970s, sure enough lightning storms set off wildfires that burned 80 to 90 percent of the park area. That’s bad enough, but the park managers decided to replant the park with a non-native grass brought in from, I believe it was, South Africa. The Anangu could have told them, if asked, that the native grass would have survived the fire and regrown all by itself.

The new grass variety, it turns out, burns at a higher, more dangerous temperature. Now when the Anangu do controlled burns they have to pull the invasive grass but the seeds remain, so the new grass is here to stay.

Today, since Handback in 1985, the park is managed jointly by the Anangu and government rangers. Both traditional and modern techniques are used. With revenue sharing, the Anangu are able to maintain their traditional culture and language. I’m told that the Anangu languages – there are two main languages and many speak several more – are relatively healthy and are taught in schools and used at home.

The morning program started with a sunrise viewing at Urulu. That meant being on the bus by 4:45 AM to be on site for the 5:30 AM sunrise. Afterward, we went for a close-up view of Kata Tjuṯa. Then back to the hotel for breakfast and down time until 3:15 PM. The afternoon ride took us all the way around Uluru, ending in a sunset viewing, complete with wine, beer and canapés. Back to the hotel for a dinner-on-your-own and bed.

Of course, “Down time” has different meanings for different folks. Judy wanted to see an art exhibit around the circle beyond Town Hall. Temperature: a balmy 107, perfect for a half-mile walk in the sun. Judy’s brother Dave sent us a message responding to the temperature saying, “Act your age.”

The art exhibit was much like what we’ve been seeing since Darwin: aboriginal works that tell stories of the artists’ community and the rules passed down over the millennia from the creatures that created mankind and handed down the laws that govern their behavior today. In the north, the work was line-based and often abstract. Here, the art was dot paintings, scenes created by dots of paint that create a whole. Just like dots on a TV screen, but much larger. All were for sale, of course.

OK, visual art’s great, but I opted for the musical arts. Actually, I was drafted to participate in what turned out to be a thirty-minute lesson, outside but in the shade, learning to play the aboriginal instrument known as the Didgeridoo. It’s a long wooden hollow pipe that you blow in to create a sound, usually a single tone (our teacher’s was tuned to F) although some variation is possible. It’s mostly a rhythmic instrument. This guy sat down in a small open-air amphitheater and started playing. Pretty soon a half-dozen folks wandered in an sat down to listen. We joined them. He immediately distributed four smaller instruments to selected audience members, including me. He proceeded to give a very detailed lesson to us beginners – not just the first step, the first four or five steps.

It’s a difficult horn to blow. It involves the diaphragm, lungs, throat, tongue and lips acting in harmonious synchronization. It involves what he called breaststroke breathing and what others term circular breathing. Sound is produced whether you are breathing in or out and so never stops. The pitch of the sound changes as the air changes direction and so the breathing must be done in time to the beat of the music. Some aboriginal groups discourage female playing; it’s a man thing.

And no, playing the tuba sixty years ago in the Hillsdale High School marching band didn’t help me one bit. As a travel experience, though, the Didgeridoo lesson beat taking a nap by a long shot.

But back to our tour around Uluru. We stopped for a hike up to the face of Uluru where we could actually touch the stone. We also saw two caves where Anangu people had etched images. Our guide said the drawings might go back 5,000 years. A placard at the cave reported that a man claimed to carved images here in the 1930s. Maybe both are correct. The walk was maybe a half mile in late afternoon sun, but still plenty warm.

Uluru was a popular climbing destination until 2018 when both Anangu and park rangers closed it down. Pollution was the big concern. Enormous amounts of trash had spoiled not only the surface of the rock, but the water table was being polluted to an unacceptable level. How hard was the climb? The number one trash item on Uluru was baby diapers (“nappies”). Batteries were right up there. On one of our walks a member of our group found a weather-worn plastic liter bottle, probably washed down from the top by passing rainstorms.

Some of the area at the base of Uluru are considered sacred to the Anangu. Why? Our guide didn’t know because the Anangu wouldn’t tell him. He is considered a neophyte and someone without advanced knowledge, learned over many years, cannot appreciate nor understand the higher levels of learning. We were asked to stop taking pictures as we drove for perhaps ten minutes along the road that circles Uluru’s base.

This sacred area is where the tour operators, after the Anangu had been evicted, built an airport to fly in tourists. And to keep the brush from growing up along the airstrip, they dumped diesel fuel, thereby polluting the ground water. That pollution is only now starting to dissipate.

Did we see any wild animals? Nope. And therein lies another story. Camels and camel drivers were imported to Australia in the 1860s to provide transportation across the desert. They were used in the construction of the Adelaide to Darwin telegraph line. At one point the Australian government, fearing an infestation, ordered camel owners to destroy what had become their pets. But instead, the camels were turned loose to live in the wild. Today, Australia has more camels, more than two million, than any country in the world. They have been exported to Saudi Arab.

Turns out, camels eat the fruit that Emus survive on. They also eat the roots of the plant. Result? Emus have had to move south to find food. No Emus at Uluru.

And how about Kangaroos? Polluted water supplies have driven them south too.

So, that’s what we learned about central Australia while taking in the beauty of the desert and Uluru. It’s hard to find anything good to say about British behavior in Australia: convict slavery and torture, aboriginal extermination, slavery from the Pacific islands, mismanagement of the lands. But then again, that list of sins applies equally well to other “civilized” nations include the good old U S of A. When will we ever learn?